Introduction

This report delves into a crucial macroeconomic issue affecting the Canadian economy: the country’s skilled labour shortage. The study aims to examine the national economy and apply relevant concepts and theories to practical challenges. While Canada has announced plans to increase immigration over the next three years to address the labour market’s pressures, experts caution that this may not solve the issue (Saba, 2023). As a result, the study aims to answer the research question, “Can Canada fix the labour shortage by merely increasing the number of immigrants?”

The report is structured around several key areas. It examines the current state of employment and unemployment in the Canadian labour market. It then considers the challenges posed by the country’s aging population and declining birth rate in the workforce. Canada’s immigration plan is assessed to identify the government’s position and goals regarding immigration’s future role in the country. The report also examines the impact of immigration on aggregate demand and supply, using supporting data and visualizations.

The study highlights the significant issue of job mismatch in the country, where many immigrants cannot fill job vacancies despite the strategic immigration plan to address the labour shortage. The report underscores immigrants’ challenges in finding employment, such as credential recognition and assessment processes. The report concludes with recommendations to address the gap between job market requirements and the qualifications of immigrants to achieve Canada’s potential output.

Data for the project were collected from official websites, publications, and web articles, and the report uses qualitative and quantitative data for analysis and visualization.

Labour Market Pressures and Immigration

Current State of Employment and Unemployment in the Canadian Labour Market

The Canadian labour market employment statistics show that this market has been performing well in the past few months, despite the challenges posed by the pandemic and rising inflation. Statistics Canada (2023) shows that the unemployment rate was 5% in February 2023.

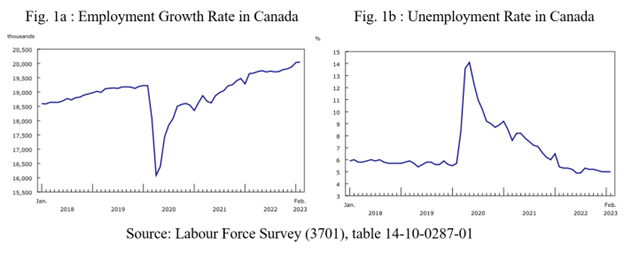

Fig. 1b shows similar trends for unemployment, with a relatively steady rate of 6% pre-pandemic with few fluctuations observed. But, in April and May 2020, the unemployment rate reached 13.6% and 14.1%, respectively, reaching its peak in the latter month. However, the rate has sharply declined since the pandemic, reaching its lowest in June and July at 4.9% and settling at 5% by February 2023.

The trend in Fig. 1a for employment growth appears generally positive, with some fluctuations along the way. From January 2018 to December 2019, employment growth in Canada showed a gradual increase, with a few fluctuations. The employment level started at 18,594.9 thousand in January 2018 and increased to 19,198.7 thousand in December 2019, with an overall growth of around 3.24%. In early 2020, employment growth experienced a sharp downturn due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The employment level fell to 18,075.0 thousand in March 2020, which fell further in April 2020 at 16,083.6 thousand, a decline of over 11% from the previous year and the lowest employment rate recorded in this dataset. However, employment started to recover gradually from May 2020, although it was still lower than pre-pandemic levels. There were some fluctuations in employment growth in the latter half of 2020 and early 2021, but it generally remained stable at around 18-19 million. The data shows that employment growth reached 20,054.1 thousand in February 2023, which was the highest point in the period covered by this dataset.

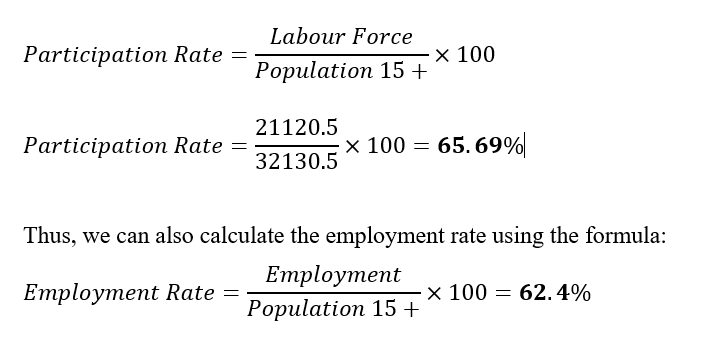

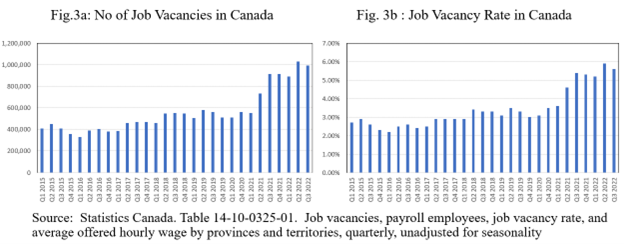

The participation rate for Canada in February 2023 was calculated using the labour force and population values obtained from Statistics Canada (2023).

Fig.2 shows a summary of the Canadian population and workforce density. Out of the total population, the participation rate is 65.7%, which can be considered good compared to the world average of 60.11%. However, this rate can be considered low compared to countries such as Qatar or Tanzania, which have 87.3% and 83.3%, respectively. Canada ranks 52nd out of 180 countries regarding the Labour Force Participation rate, as The Global Economy (2023) reported.

Canada has an employment percentage of 62.4% of its total population, ranking it 42nd among the countries with the highest employment rates, according to Trading Economics (2023). In comparison, the United States is ranked 48th with a 60.2% employment rate. Despite having a higher employment rate than the US, Canada lags behind countries like the UK and Germany, which have employment rates of 75.7% and 77.3%, respectively, making them more employable.

Current Job Vacancies in the Canadian Labour Market

With unemployment at a natural rate of 5%, and a labour force of 65.7% of the population, we contemplated the question; why is there a need for immigration or any other external intervention in the labour market?

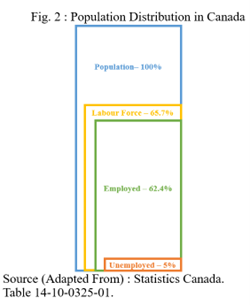

As per the data obtained from Statistics Canada (2023), there are around 100,000 job vacancies in the current labour market, as shown in Fig. 3.

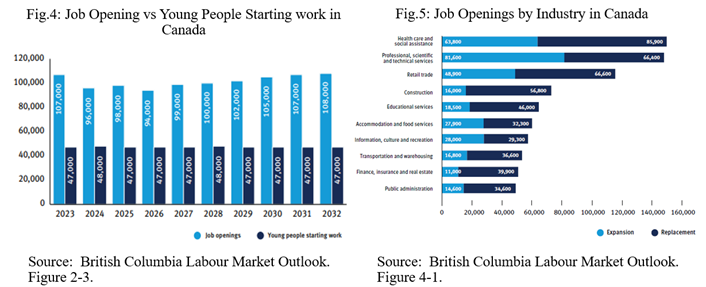

The number of job vacancies and the vacancy rate has been rising steadily, which reached its peak in Q2 of 2022 at 1,031,955 job openings. Therefore, despite having a low unemployment rate, Canada has a labour shortage that must be filled to reach economic goals. This shortage will only grow in the coming years, as shown in Fig. 4. which shows the number of job openings in British Columbia from 2023 to 2032 against the number of young people starting work in the same years.

The data shows that, on average, 51,900 young people will join the workforce every year in British Columbia, but the number of job openings ranges from 96,000 in 2024 to 108,000 in 2032.

The healthcare and social aid sector is expected to have the highest number of job openings in British Columbia from 2022 to 2032 (British Columbia Labour Market Outlook, 2023). Out of the total job openings, 57% will be due to the need to replace workers who are leaving the industry, while the remaining 43% will be due to growth in the health system to meet the needs of the aging population, mental health and substance abuse issues, and expansion of the Care Economy. Furthermore, the professional, scientific, and technical services industries are also expected to proliferate, with economic growth driving 55% of the expansion job openings in this sector.

Effect of Aging Population and Declining Birth Rate on the Canadian Labour Market

The primary reasons for the increase in job openings and vacancy rates (other than economic growth) are Canada’s aging labour force and dwindling fertility rate.

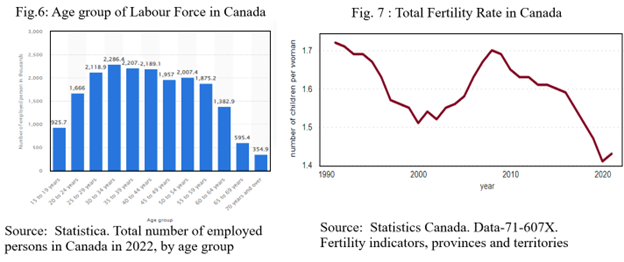

Fig. 6 shows the age groups of employees working in Canadian workplaces (Statistica, 2023). According to the dataset, 30 to 34-year-olds account for the highest number of workers at 2.28 Million, along with 35 to 39 and 40 to 44-year-olds at 2.21 Million and 2.19 Million, respectively. The cause for concern is that there are 2.33 Million workers aged 60 and above, and they account for 11.92 % of the workforce. These people are expected to retire soon, leaving a significant gap in the labour market.

Moreover, Figure 7 illustrates the fertility rate in Canada over the last 40 years. Since the 1990s, the fertility rate has been dropping steadily, reaching its lowest in the 2000s at just 1.5 children per woman.

However, the rate started to climb since then, reaching its peak at 1.7 in 2008. The increase was because more older women aged 35 to 44 started to have children (Statistics Canada, 2015). However, since the 2010s came around, this rate started falling, reaching its lowest in 2020 at 1.41 children per woman. One factor off reduction in children born is the rising cost of raising a child, which has made fewer people opt to have children. Additionally, women in the Western world are becoming more socially empowered and have higher levels of education, leading to a downward trend in fertility rates and a reduction in the number of children going to school. Since then, the rate has somewhat increased in 2022 and is on a positive trend, but it is insufficient to rely solely on Canada’s economic growth.

Hence, the aging workforce and low fertility rates have reduced the national population workforce and forced the government to increase immigration. Immigrants account for 23% of Canada’s total population (Sivakumar, 2023), which is projected to only increase due to the current and future labour market shortage.

Governments Immigration Plan

The prosperity of Canada’s economy is partially determined by the number of individuals in the labour force and contributing taxes to support public services like healthcare and pension plans. Immigrants play a significant role in the economy by filling gaps in the labour force and contributing to tax and consumption. Therefore, without immigrants, employers would struggle to locate enough qualified individuals to fill open positions.

As per the IRCC (Government of Canada, 2023), Canada succeeded in its aim of welcoming 431,645 fresh permanent residents in the preceding year, surpassing the target for 2021. The government intends to boost the number of immigrants settling in Canada over the following three years to combat labour shortages in different industries. According to the 2023-2025 Immigration Levels Plan (Government of Canada, 2023), new targets have been established to bring in 465,000 new residents this year, 485,000 in 2024, and 500,000 in 2025.

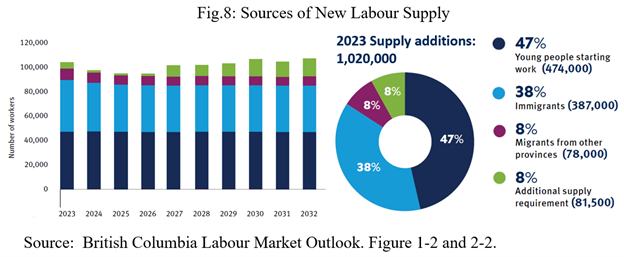

For example, according to the BC government, as shown in Fig. 8, the most significant contributor to the labour force will be young people entering the workforce at 47%. Followed by international immigrants at 38%, contributing to 387,000 jobs in 2023. The government of Canada will need to bring in increasing numbers of immigrants as planned because the requirements for skilled workers is increasing, and “many companies are starved for workers,” as mentioned by Ravi Jain (Saba, 2023).

According to the 2022 BC Labour Market Outlook, an average of 39,000 new immigrants will join the labour force annually in British Columbia over the next ten years. The numbers are expected to vary from more than 42,000 in 2023 to almost 38,000 in 2032.

Impact of Immigration on Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply

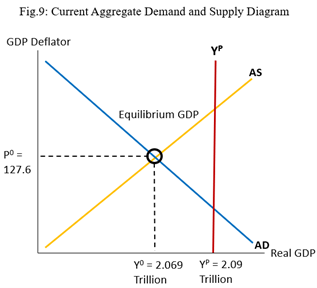

An aggregate demand and aggregate supply chart shown in Fig. 9 were plotted using the GDP Deflator value against the Real GDP of Canada. The GDP Deflator value was obtained from Trading Economics (2023), which was 127.6 in Jan 2023. Moreover, the Real GDP value was obtained from Ycharts (2023), which was 2.069 Trillion in Jan 2023. Also, since Canada is in a recession phase, there is a gap between the equilibrium GDP and potential GDP, which was -0.949%, as reported by CEIC (2023).

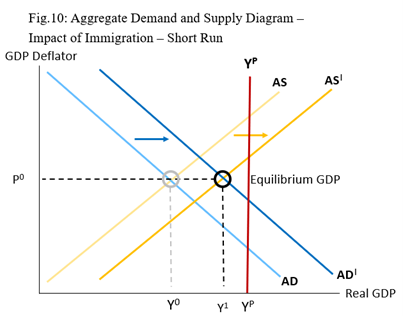

Short Run:

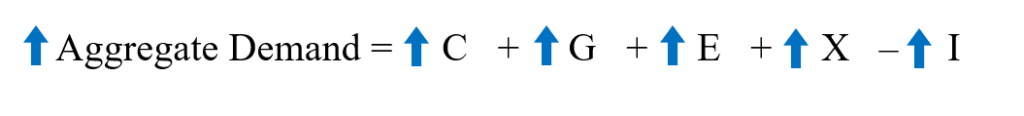

As we know that the aggregate demand consists of :

Consumption + Investment + Government Expenditure + ( Exports – Imports)

When the net inward migration grows, so does the country’s population. This could result in a higher percentage of migrants who are paid workers (than before), increasing the overall income. This higher income causes greater investments and consumer spending on goods and services at every price level, hence increasing tax revenues for the government, causing increased expenditure. Since there would be more labour force, the number of imports and exports to and from Canada would also increase. Therefore, the aggregate demand would increase in the short run, and the curve would move to the right.

On the other hand, aggregate supply illustrates the total output of goods and services produced at different price points. When the net inward migration grows, there is an expansion in the active labour force, which increases Canada’s productive potential. This also increases the stock of human capital (not just the quantity but the quality of labour) in the Canadian economy. Hence, this increases labour productivity since more experienced and qualified workers would enter the labour force. Therefore, the economy could produce more goods at every price level. Thus, the aggregate supply increases in the short-run, and the curve moves to the right.

Both aggregate demand and supply would be closer to the potential output in the short run, denoting that Canada’s real GDP is closer to the potential GDP than before. Using the above analysis, we can plot the new aggregate demand and supply curves in the short run.

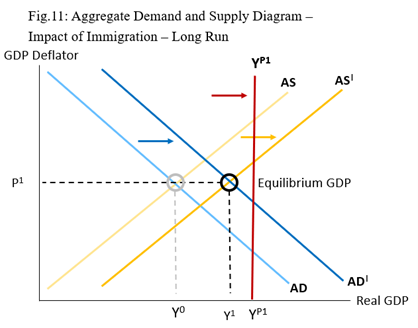

Long Run:

Aggregate demand would continue to increase in the long run as new skilled workers settle permanently in Canada; they would also increase the country’s population, potentially leading to a higher demand for goods and services in the long run. This could shift the aggregate demand curve to the right and can lead to a sustained increase in aggregate demand over time.

The increase in skilled workers in the labour force could increase the economy’s potential output, as they could bring in new skills and knowledge that can help improve productivity and innovation in various sectors of the economy. This could increase the long-run aggregate supply and move the long-run aggregate supply curve to the right. This can help the economy adjust to the increase in aggregate demand and ensure no inflationary pressure in the long run.

We can plot the long-run aggregate demand and supply curves using this analysis.

Challenges Faced by Immigrants

Skills Mismatch

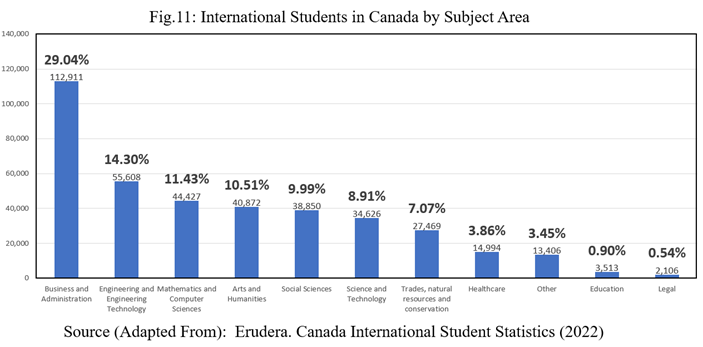

According to Statistics Canada (2023), new immigrants who have recently come to Canada are less likely to use their skills and education than Canadian-born workers. A lawyer in Toronto specializing in immigration says that government policies are causing a problem because the specific skills employers are looking for do not match the skills of immigrants who are approved to come to Canada (Saba, 2023). This problem starts with international students. Many plan to stay in Canada after graduation, but they are not studying for jobs that are in demand by immigration policies. They are studying to get PR and residency, which is a significant cause for concern.

Fig.11 shows the percentage of international students enrolled in each subject area. There are 388,782 international students in Canada, as Erudera (2022) reported. As can be seen, most of the international students are enrolled in Business and Administration courses at 29.04%, followed by Engineering courses at 14.3% and Maths and Computer Sciences at 11.43%. The lowest studied courses are Education and Legal at 0.9% and 0.54%, respectively.

According to the BC Labour Market Outlook data shown in Fig. 5, the highest number of job openings are in areas such as healthcare, professional services, technical services, scientific services, retail, and construction. Healthcare subject, for instance, only accounts for 3.86%, as only 14,994 students are currently studying this subject, but the number of job openings in this sector will be 149,700 in 2023. This shows that there will still be a significant shortage in the labour market even after these international students graduate. Another example of this mismatch is the education sector, which only has 3,513 international students, while the number of job openings will be 64,500. These cases show that even though students are coming to Canada and enrolling in educational institutions, they are not necessarily studying for jobs with a labour market shortage.

Note: Canadian students will also help alleviate the pressure on the labour force shortage; however, the student numbers shown are only for international students.

Overqualification

More than 25% of immigrants with foreign degrees were overqualified for their jobs in Canada, as J. Wong (2022) reported. Canada is failing to recognize the training and qualifications of workers educated abroad once they are there and is “leaving talent on the table.” This mismatch extends to high-demand sectors, such as healthcare, which have been under tremendous strain amid the COVID-19 pandemic, with just 36.5% of foreign-trained immigrants working in registered nursing and only 41.1% of those with foreign medical degrees working as physicians. Canada needs to do a better job recognizing and accrediting immigrants’ credentials.

In times of economic recession, when joblessness is rampant, highly skilled workers might stop searching for a job that matches their abilities and instead would accept a lower position that does not utilize their complete skill set. This leads to immigrants being overqualified for the jobs they are working.

Recommendations

Below are some recommendations for immigrants and the Canadian Government:

Credential Recognition in Canada

Individuals new to a particular field and wish to work in jobs that demand a license or certificate must ensure that their foreign licenses and certificates are acknowledged. This process involves verifying that the training, education, and experience obtained in another country satisfy the federal, provincial, or territorial standards (Government of Canada, 2023). Newcomers to Canada who are underemployed in positions that do not match their skills and experience can feel disheartened as they cannot utilize their previous learning and expertise. Not acknowledging their credentials can lead to losses for both immigrants and taxpayers.

The Government of Canada provide a Guide that can help immigrants coming to Canada how to prepare to work in their chosen profession. It outlines the steps they can take to compare their qualifications with their chosen job and province requirements, communicate with the relevant regulatory body or authority, and consult an approved assessment agency. This would create more opportunities for immigrants to upgrade their skills and education and integrate effectively into the Canadian labour market.

Special Round of Invitation for In-demand Jobs

The Canadian government can consider implementing a Special Round of Invitations for In-demand Jobs, which would have lower CRS (Comprehensive Ranking System) scores and more frequent invitations for these jobs. The Comprehensive Ranking System is a point-based system used by the Canadian government to rank the profiles of candidates in the Express Entry pool. It assesses candidates based on age, education, language proficiency, work experience, and other criteria.

By having a Special Round of Invitation for In-demand Jobs, the Canadian government can prioritize selecting candidates with the skills and expertise currently in high demand in the Canadian labour market. This can include jobs such as healthcare professionals, engineers, IT professionals, and others. The government can also lower the CRS scores for these candidates, which can help the government streamline the selection process and expedite the entry of skilled workers into the Canadian labour market.

Fiscal Policy Changes

The government’s immigration plan may require fiscal policy changes to support the integration of new permanent residents into the labour market. For example, the government may need to allocate funds to support language training or to provide financial incentives for employers to hire new immigrants. These types of government spending programs could be considered part of fiscal policy. The government could also implement tax incentives for companies to invest in training programs for new employees or provide subsidies for companies to hire new workers in specific industries.

Increasing Labour Force Participation

Canada can tap into a larger pool of potential workers and reduce its reliance on immigration by increasing its labour force participation rate. This can be achieved by implementing policies and programs encouraging individuals to enter or re-enter the workforce, such as offering training and education programs, flexible work arrangements, and child care support.

Diversity and inclusion have become progressively more significant in the workplace, not only from a social and ethical standpoint but also from a business perspective. Many underrepresented groups, such as indigenous people and individuals with disabilities, face systemic barriers and discrimination in the workplace. By investing in training programs and actively recruiting from these communities, businesses can help break down these barriers and provide opportunities for individuals who may have previously been overlooked. This can help grow the labour force participation in Canada.

Industrial Automation

Another way to meet Canada’s need for additional workers is through the increased adoption of automation. Automation can help businesses to streamline their operations and increase productivity.. This would decrease the amount of people required to work in the labour force, reducing the need for more immigrants. Automation can also create new job opportunities for workers with skills in technology and engineering.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Canadian labour market has been performing well in recent months despite the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic and rising inflation. The unemployment rate was at a natural rate of 5% in February 2023, and employment growth has been generally positive, with some fluctuations along the way. However, despite having a low unemployment rate, Canada has a labour shortage that must be filled to reach economic goals. The number of job vacancies and the vacancy rate has been rising steadily, which reached its peak in Q2 of 2022 at 1,031,955 job openings.

The healthcare and social aid sector is expected to have the highest number of job openings in British Columbia from 2022 to 2032, with 57% due to the need to replace workers leaving the industry. Additionally, the impact of an aging population and declining birth rates will further exacerbate the labour shortage in the coming years.

To address the labour shortage, the Canadian government has introduced an immigration plan to bring in 401,000 new permanent residents in 2023, increasing to 421,000 by 2026. Immigration can have a positive impact on aggregate demand and aggregate supply. However, immigrants may face challenges, such as credential recognition and skills mismatch, that may affect their ability to find employment in their field of expertise.

The Canadian government should focus on initiatives to help immigrants overcome the challenges they face and integrate into the workforce. They could do this by ensuring proper credentials recognition, having special rounds of invitation in the Express Entry pools for in-demand jobs, changing the fiscal policy, and helping increase labour force participation. Additionally, the government should support investments in training and education programs that target the high-demand sectors of the labour market. Finally, businesses should consider hiring and investing in training programs for underrepresented groups, such as indigenous people and individuals with disabilities. This would help diversify the workforce further and ensure sustainable growth of the economy.

References

D’Andrea, A (2023, March 10). Canada’s federal budget for 2023 will be released on March

28: Freeland. Global News.https://globalnews.ca/news/9542502/canada-budget-2023/

CEIC. Canada GDP: Potential Output and Output Gap: Forecast: OECD Member: Annual.

https://www.ceicdata.com/en/canada/gdp-potential-output-and-output-gap-forecast-oecd-member-annual

Government of Canada (2022, November 1). Notice – Supplementary Information for the 2023-

2025 Immigration Levels Plan. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/news/notices/supplementary-immigration-levels-2023-2025.html

Government of Canada (2022). CIMM-2022-224 Multi-Year Levels Plan-February 15 & 17,2022

Saba, R(2022, February 1). Canada’s immigration increase alone won’t fix the labour market,

experts say. CTV News. https://www.ctvnews.ca/business/canada-s-immigration-increase-alone-won-t-fix-the-labour-market-experts-say-1.6255154

Sivakumar, V. (2023, February 9). Why birth rates are low in Canada and much of the Western

world. CIC News.https://www.cicnews.com/2023/02/why-birth-rates-are-low-in-canada-and-much-of-the-western-world-0232764.html#gs.sanraa

Statistics Canada. (2023, March 10). Labour Force Survey, February 2023.

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/230310/dq230310a-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2022, December 19). Job vacancies, payroll employees, job vacancy rate,

and average offered hourly wage by provinces and territories, quarterly, unadjusted for seasonality.https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1410032501&cubeTimeFrame.startMonth=01&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2015&cubeTimeFrame.endMonth=10&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2022&referencePeriods=20150101%2C20221001

Statista. (2023, January 17). Total number of employed persons in Canada in 2022, by age

Statistics Canada. (2022, December 19). Job vacancies, payroll employees, job vacancy rate,

and average offered hourly wage by provinces and territories, quarterly, unadjusted for seasonality.https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1410032501&cubeTimeFrame.startMonth=01&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2015&cubeTimeFrame.endMonth=10&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2022&referencePeriods=20150101%2C20221001

Statistics Canada. (2015, November 27). Change in births.

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/84f0210x/2009000/part-partie1-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2022, September 02). Business output growth outpaces growth in hours worked for the

first time in eight quarters. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220902/cg-a001-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2023, March 21). Consumer Price Index, monthly, not seasonally adjusted.

Consumer Price Index, monthly, not seasonally adjusted (statcan.gc.ca)

The Global Enomy.com. (n.d) Labor force participation – country rankings.

Labor force participation by country, around the world | TheGlobalEconomy.com

Trade economics. (n.d) Canada GDP Deflator.

https://tradingeconomics.com/canada/gdp-deflator

YCHARTS. (n.d) Canada Real GDP (I:CARGDP)

https://ycharts.com/indicators/canada_real_gdp

Erudera. (2022) Canada International Students Statistics

https://erudera.com/statistics/canada/canada-international-student-statistics/